So far, we have seen the Model and Update part of the navigation application. In this blog, we complete the whole project by connecting the final missing piece View. First, let’s look at the output.

The first two lines on the screen are the two links—one to ‘All-Time Best’ and another to ‘Login.’ By default, ‘All-Time Best’ is set as Home, and if we pass any routes other than ‘Login,’ all routes will be routed to ‘All-Time Best.’ On page load, the page will look like the following; It loads ‘All-Time Best’ view.

When you click ‘Login,’ it will display the following.

In this example, if you notice, we have two sections, one is the top section, which contains hyperlinks to navigate, and then the view right below it to show the page’s content. For simplicity, we call the top section as header and the second part as the body. So view will contain the header and body.

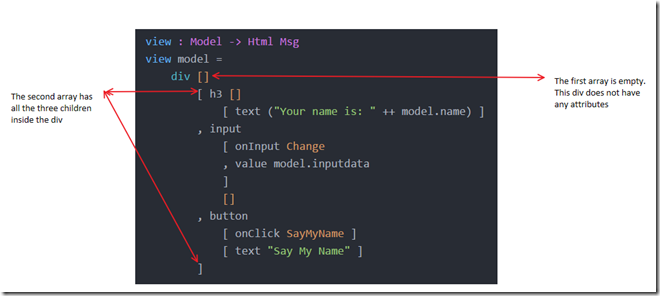

view: Model –> Html Msg

view model =

div []

[ header

. body model

]

Like all the Elm applications, the view takes the model as input and generates the Html to generate messages. The model has two functions: header and the second one is body, which takes the model as a parameter.

Let’s review the header function first.

header: Html Msg

header =

div []

[ h3 []

[ a [ href “#alltimebest” ] [ text “All Time Best “ ]

, a [ href “#login” ] [ text “ Login” ]

]

]

The header function takes no parameter but generates Html. This function creates two hyperlinks (a tag). The only thing we need to pay attention to is the first parameter to href function. This string must match the strings in the update function.

case (hash) of

“#alltimebest” ->

AllTimeBest“#login” ->

Login

Next, let’s define the body function.

body:Model –> Html Msg

body model =

case (model.page) of

AllTimeBest –>

alltimebest model

Login –>

login model

As you can imagine, we need to make sure we display an appropriate body based on the page requested. We did not display anything during the update function—all we did to change the page to the appropriate page in the model. Based on the page information in the model, we need to make sure we need to render appropriate content.

Based on the output we saw earlier, the all-time best and login function has nothing but a text to show page change happened. The function definitions of the pages are below.

alltimebest: Model –> Html Msg

alltimebest model =

h1 [] [ text “All Time Best” ]

login: Model –> Html Msg

login model =

h1 [] [ text “Login “]

Events leading up to view are

- When someone wants to change a page, they click on the hyperlink

- when the hyperlink is clicked, elm generates a navigation message (UrlChange)

- The message triggers the update function

- In the update function based on the change request, we create a new model with the page type requested

- On completion of the model change, the view function is called

- the view will turn around and call the body function with the current model

- In body function, we check the model’s page type. If the page type is AllTimeBest then we call the ‘alltimebest’ function to create Html otherwise, we call Login

In summary, navigation is straightforward and simple in Elm. The things we need to know are

- Use Navigation.program to connect Model, Update, and View

- Have Model with the field which can hold the current page

- In an update, handle Urlchange event with location parameter to change the Model

- In view, use the Model’s current page to render the page in question